When someone sends me a list of items to negotiate using an e-auction, one of the first questions I ask is: “What is your award scenario?” While a procurement professional should consider this question long before a negotiation, Request for Proposal, or even before polishing up the category strategy, many have not. The award scenario determines how the potential business will be divided up between suppliers (Winner take all? Cherry-pick?) and so determines the structure of any bids from suppliers. As with almost all aspects of procurement, each option has pros and cons and implications for the overall procurement strategy. Today’s article is about potential award scenarios, when they are useful, and pitfalls of each option.

Winner Takes All

One of the most common award scenarios is when one supplier wins all of the business. For a lump sum bid or bid with only one line, winner takes all is the default option. This option is easy to award, easy to administrate, and easy to determine which supplier offers the best value.

When winner takes all is useful: Awarding all business to one supplier is best when the complexity of the category is low, or when the supplier is handling the complexity and when leverage with the category is low. Examples include awarding capital projects to one general contractor, awarding a full vendor-managed inventory program, or bidding out a low-spend/tail spend category.

Pitfalls of winner takes all: The biggest pitfall of winner takes all is that it puts all of your risk and reward with one supplier. If something happens to that supplier, they don’t perform, or they have a major supply chain disruption, you may have to scramble to find another source.

Cherry-pick

Cherry picking is when a supplier is awarded work based on their value for each individual line in the bid. For a list of parts, this means suppliers would only win the award for the individual parts where they offered the best value. The best value is often price, but there may be an equation for rating faster lead times or other factors in addition to price. When running a cherry-pick bid, each component or line item almost functions like a mini-bid because its award does not affect the other items.

When cherry picking is useful: Selecting each line for the best value is best when getting to the absolute maximum value or bottom dollar is essential. In a true cherry-pick bid, you aren’t ever losing out on the best value from trying to concentrate the spend on fewer suppliers. Cherry-pick awards work best in fractured markets with suppliers who are hungry for any amount of business.

Pitfalls of cherry picking: The biggest drawback of a cherry-pick award is that sometimes an ERP system is not set up to manage all the complexities of awarding each item to an individual supplier. It is also critical to have part numbers so you can load the right supplier, price, and lead time associated with that part number. If you run an ERP system without pricing by part number, you are inviting noncompliance to the carefully crafted cherry-pick award. Cherry-picks also can reduce leverage with suppliers who are not being offered a block of business. Suppliers tend to want the full block of business for the bid or category and will not throw in any value-added extras on a cherry-pick award.

By Subcategory

Awarding a bid by subcategory means grouping together pieces of the award based on their subcategory. For example, on a safety supplies bid you might award gloves to one supplier, hard hats to another, and safety glasses to a third. Awarding by subcategory might be driven by an ERP system with a very deep category taxonomy or it may be based on what the suppliers bidding can offer.

When subcategory awards are useful: Awarding by subcategory usually comes about because certain suppliers only offer pieces of a whole bid. I’ve seen it happen where the intent was a winner-takes-all bid, only to have it awarded by subcategory because one high value supplier had a gap in what they could supply (in our safety supplies example, perhaps one supplier could provide gloves and safety glasses, but they could not supply hard hats or the pricing on hard hats was very high).

Pitfalls of subcategory awards: Making an award based on subcategory combines some of the pitfalls of both the cherry pick and the winner takes all approach. The buyer puts all of the risk on a subcategory with one supplier, but also erodes their leverage in the market by not offering as much business to the winning supplier. It is difficult to predict this award scenario before receiving bids, so a buyer needs to be flexible and creative for this solution to work.

First Phone Call (or Right of First Refusal)

The first phone call approach means the awarded supplier will be the first one called for business in the bid category. I see this most often with service or labor bids, such as plumbing suppliers for plant maintenance. When planning on a first phone call award, typically the bid is a sample project similar to the one the supplier would provide. Often there is a full hierarchy established in these bids with a list provided to the technical team on which supplier to call first, which to call second, etc.

When first phone call is useful: The first phone call award scenario is most useful when the category’s spend is very unpredictable and there isn’t time to bid out each need when it arises. When a plant needs a plumber, chances are good there isn’t time to go through a procurement bid cycle. The first phone call award is also good when the category is highly variable in scope, such as when a repair crew might sometimes have a small fix but other times might be there for a week fixing a large issue. Lastly, the first phone call award can be useful when there is more work available than one supplier can handle, so the “spillover” work can go to the next supplier on the list or the first supplier who has a crew available.

Pitfalls of the first phone call award: The biggest issue with first phone call is compliance. A technical team will tend to simply call their favorite supplier on the list instead of calling suppliers in the awarded order. The next biggest pitfall is that suppliers have almost no estimate or guarantee of work, so they may not be incentivized to make their best offers. When building a bid for a first phone call award, the buyer also needs to pick the right sample project(s) and make them as realistic and accurate as possible. This might mean pulling old invoices and building a sample scenario or two based on previous events. Do not simply add up all labor rates and bid that total (as addressed under “Time and Materials” in this article).

Allocated Percentage

An allocated percentage means you intentionally award some of the business to a secondary or even tertiary supplier. This is a way to mitigate risk and is a technique typically used by more mature supply chain teams because it requires more management. The percentages can vary, but an allocated percentage might mean awarding 80% of the work to a primary supplier and 20% to the secondary, or it might mean 50% to the primary, 30% to a secondary, and 20% to a tertiary (or any other set of percentages).

When allocated percentage is useful: The allocated percentage is best when trying to mitigate risk and keep a secondary or tertiary supplier available to supply. In the supply chain disruption following COVID, many supply chains intentionally awarded some work to a higher-price supplier in order to help ensure material would continue to flow. The allocated percentage model is also good when trying to develop a new supplier, especially a small diverse supplier. Giving 10% of the business to a new supplier can help them understand expectations, develop a track record of success, and build that relationship.

Pitfalls of allocated percentage: Allocating a percentage of business can be difficult to manage. The best way I have found to do so is with a good blanket PO program where you set the blanket PO amounts to the expected spend percentages for each supplier. If one blanket runs out of spend prematurely, then you know your spend percentages are off and you can adjust. The other pitfall of an allocated percentage is you have to be very clear with suppliers on what work they will win, how you will manage it, and ensure the percentages for all suppliers are worth winning. It does not work well to use an allocated percentage with a small spend category because it is not appealing enough for suppliers to win only 20% of a small amount of business.

Overall Thoughts

While these are the basic award scenarios, others exist and many of them are simply combinations of the above options. For example, awarding work by location or plant is a combination of cherry-picking (by plant) and winner takes all (everything within that plant).

When possible, it is helpful to set the potential award scenario ahead of any RFP or negotiation/e-auction. If you have no idea how to set an award scenario, that might be a good opportunity for an RFI ahead of the RFP. Reminder that RFIs (Requests for Information) should not have any pricing included and should truly be to gather information and not to gather initial quotes (pricing is for an RFP or RFQ). Communicating your award scenario to suppliers helps build the supplier relationship and adds to the transparency of a bid.

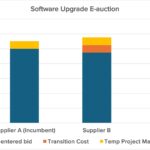

When setting up an e-auction, it is very important to know your award scenario ahead of running the e-auction (even if you are setting or changing it based on RFP information received). This is because e-auctions have to be set up so the awards fall how you intend, with each lot awarded to one supplier. If multiple lines are all intended to be awarded to one supplier, they need to be set up within one lot in the e-auction. Suppliers also need to know if 2nd or 3rd place has value in an auction (such as in the scenario with an allocated percentage).

Hopefully this discussion adds clarity to your category and bid strategies, and gives you a few more options than the standard cherry-pick or winner takes all options. If you’d like to talk about your award scenario strategies, let’s chat. If you’d like to get these articles weekly straight to your inbox and never miss one, sign up for my newsletter.

My book, Transform Procurement: The Value of E-auctions is now available in ebook, paperback and even hardcover format: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0F79T6F25