Once the procurement team orders goods and the inbound logistics team ensures they arrive, the warehouse team ensures they are delivered safely and accurately to their final destination. So why is the warehouse so often part of operations instead of the supply chain? Today’s article talks about the pros, cons, and considerations for where the warehouse fits in a company’s organization as well as some initial steps for better supply chain alignment.

The Org Chart

When we discussed the reporting chain for a supply chain leader, the most common locations were under the COO, CFO or the CEO. The decision made here can and should echo through to the warehouses. The easiest option for warehousing to report to the supply chain leader is when the supply chain leader reports to the COO or operations leader. The most common place to find warehousing in a company org chart is under operations, so this is the shortest jump to keeping the warehouse reporting under the supply chain.

The tricky part of moving the warehouses into the supply chain team is that sometimes scheduling, planning, or S&OP are considered part of the warehouse, and those areas are less clear if they belong under the supply chain umbrella. If your supply chain is mature and complete enough that planning is part of the supply chain cycle, then this decision is easier. But for many companies, planning is still somewhat unstructured, ad hoc, or immature and may not have specific personnel responsible for planning roles. If this is the case, consider building out these roles within the supply chain team first instead of starting them as part of operations.

I am generally an advocate for the warehouse team reporting up through the supply chain leader, regardless of who directly supervises that supply chain leader.

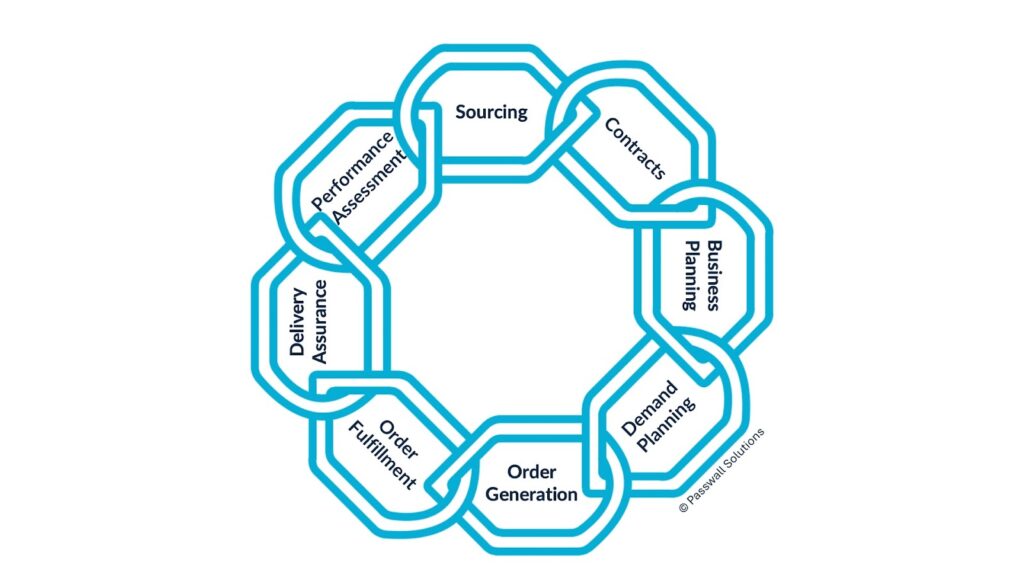

The Supply Chain Cycle

The supply chain cycle includes Delivery Assurance, which includes warehousing. One of the most common issues I see in supply chain teams is the struggle to hold people accountable for their categories and on-time delivery. While sometimes this is caused by too many approvals, more often it is due to siloed teams handing off work and simply “throwing it over the wall” to another team to manage. A buyer or category manager is responsible for an item until it is put in the hands of the person who needs it. In manufacturing, this might be delivering the item to the assembly line. In utilities, it might mean loading up the line worker or contractor truck to go out into the field. With a service, it might mean double checking that the supplier provided the report/download/software license on time and complete to the correct person.

In any industry, the supply chain or purchasing team cannot simply wash their hands of a purchase the minute they send the first PO. Nor can they remove themselves from the equation as soon as the warehouse receives the item. If the ordered good or service is needed and is missing, the supply chain team will be that stakeholder’s first phone call. Making sure that stakeholder gets a good answer is worlds easier if the warehouse is part of the supply chain team.

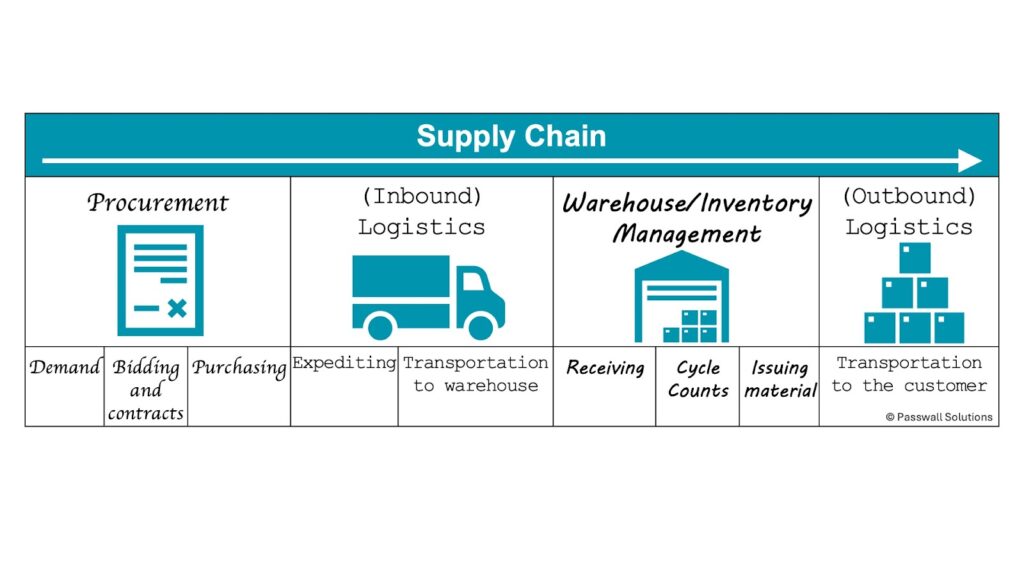

The Definition of Supply Chain

People define supply chains in multiple ways. My personal favorite definition is that “supply chain” covers the full supply chain process from demand to delivery to the final customer. The three main categories I consider as part of the supply chain are procurement, logistics, and warehouse or inventory management. Using this definition, the warehouse is fully a third of the supply chain process and provides that vital last step between the supply chain team and the next downstream stakeholder.

Ultimately, all signs point to the warehouse as part of the supply chain and indicate procurement, logistics, and warehousing should all be part of one, big (sometimes happy, sometimes not-so-happy) supply chain family. So what if the warehouse reports up through an entirely different organizational chain from procurement or logistics?

Aligning the Supply Chain Teams

The ultimate goal is excellent alignment between the components of the supply chain, regardless of their reporting structure. To achieve this alignment, start with at least one of the following actions:

- Consciously connect procurement, logistics, and the warehouse. Ensure there are regular formal and informal interactions between the teams so they form personal relationships. This might mean regular check-in meetings to troubleshoot issues with ordering and receiving. It also means sending buyers and category managers to the warehouse to help with physical inventory and cycle counts. It’s very important that the warehouse team see the procurement and logistics teams as more than “desk jockeys” or “truck jockeys.” It’s also important the procurement and logistics teams really see and experience the challenges the warehouse faces with space management, moving inventory around safely, and the demands of their downstream stakeholders.

- Elevate the attention on invoice holds and ensure the right team members are held accountable. Invoice holds are when the supplier sends an invoice for payment, but it is held because there is a mismatch between PO and invoice, there is a system issue, or the part has not been received by the warehouse. I have very frequently seen purchasing teams held highly accountable for invoice holds (even affecting their annual bonuses) when the majority of invoice holds are due to parts not being received in the system for weeks or months. Make sure the right invoice hold issues are assigned to the right stakeholders.

- Make a plan to align the org chart. This might be a gradual plan, perhaps starting with larger “hub” warehouses or distribution centers, but get the warehouses under the supply chain leader. I knew a manufacturing supply chain leader who started at the organization without the warehouse function in his org chart. He gradually worked at pulling them into the fold, integrating planning functions all along the supply chain cycle as he went. While COVID was as hard on that team as anyone else, the alignment of his procurement, logistics, and warehouse team meant information about missing or critical parts for the assembly line reached the right category manager more quickly and they were able to implement their contingency plans faster to get the missing parts to the line. Invoice holds also went down dramatically, and during slower production periods he had more freedom to move staff to the warehouses who needed help.

While I am ultimately an advocate for aligning the warehouses under the supply chain leader in a company, there are exceptions to every rule. Perhaps there is a regulatory reason to keep the teams separate. Or perhaps the warehouse team is so small for a more service-oriented company that it’s simply a non-issue. Either way, keep your eye on aligning these teams as much as possible, regardless of where they fit in the chain. And if you’d like to talk through your own org chart and how to improve supply chain alignment, let’s chat.