Some months ago on LinkedIn, I saw an account rep run a poll about all the questions he had to answer for a Request for Proposal (RFP), asking his fellow sales team peers about their experiences with long question lists. This struck me because my reaction was: why is the procurement/technical team asking all these questions at all? That conversation keeps rattling around in my brain alongside other things that make an RFP more appealing. So today’s article talks about those long lists of questions, redefining them as criteria, needs vs. wants, when to use an RFI, and writing a more monetarily appealing RFP.

Long Lists of Questions

We’ve all seen them, and some of us have written them: long lists of questions for the sales team and supplier technical teams to answer. These are especially common in service or indirect bids where the scope of work is less defined than with a material or widget. These questions might look like:

- What is your schedule for implementation?

- Describe your plan for the initial work scope.

- What is your experience with projects similar to this one and what were their results pertaining to budget and timeline?

- Describe your supplier diversity program and your current diverse supplier percentages.

- List the subcontractors your business may use to accomplish this scope.

- Explain your cybersecurity program and history.

- Provide three references for similar work scopes to this one.

- Etc.

While these are well-meaning and very common (how many of the above have you seen before, verbatim?), they also send a few messages to sales teams. When I read scopes of work with questions like this, it tells me:

- The team may be willing to choose a supplier based on who has the glossiest 4-color brochure or most expensive-looking PowerPoint.

- The technical team doesn’t really know what they’re wanting to buy.

- The procurement professional running this bid might not be very familiar with this category (especially true if the questions are very generic instead of specific to the scope).

- There is an audit or compliance team internal to the company requiring the company to gather certain data from their suppliers.

- The company has some sort of vague “bad experience” with a subcontractor out there they’re trying to avoid, but don’t want to state it (and it may have even been more than 10 years ago).

Lots of suppliers see long, complicated lists of questions and increasingly respond “I don’t have time for this.”

First Steps

So what do we, as procurement professionals, do when presented with a scope of work containing a long list of complicated questions? The first step is to ask: who wants these answers and who will truly read them? If the technical team is asking for references, who on the team is designated to call the references and what questions will they ask? When a scope of work is written by a committee of employees, it tends to get a bit bloated with “just in case” questions. Everyone else assumes someone else on the committee will take the time to read these answers. But will they? Unless there is a dedicated team member to make phone calls to references, consider getting rid of that section. And don’t allow the technical team to designate the procurement rep – the point should be to ask detailed technical questions that a procurement team member is not likely to know to ask. Assign an “owner” to each question the technical team is asking suppliers – the person who needs that answer. If you cannot find a technical team member willing to own the question, throw it out.

Now that we have identified which questions a technical team member truly cares about, ask why they care. Why do they want to know about past experience? Why do they want the subcontractor list? What are they looking for in a cybersecurity program? Now replace the question in the scope with the answer to that question. If they want to know about past experience so they are sure the supplier can do the work, instead turn it into a more go/no-go criteria requiring suppliers to have three similar projects completed within the last five years. Instead of requiring the subcontractor list from each supplier, publish a list of approved or prohibited subcontractors. As a procurement professional, push back if a subcontractor is prohibited because “we had an issue with them 15 years ago.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard that in my years working with indirect scopes of work. Instead of asking about the cybersecurity program, require that the supplier passed a SOC 2 audit and has a dedicated cybersecurity team. Don’t make suppliers guess the answers, tell them what will disqualify them so suppliers don’t waste their time.

Needs vs. Wants

Often a list of questions contain a few along the lines of “tell us how you would do X.” Or “Explain your capabilities around [an additional scope not outlined in the main scope].” This is where a technical team is exploring options, additions, and other value-add activities that aren’t truly required to meet the need. These are in no way a bad thing, and can often differentiate suppliers when a company is focused on the total cost of ownership. But hiding them in the list of questions both makes them hard for a supplier to identify as optional and can cause confusion.

Rather than incorporating added possibilities into the long list of questions, pull them together into a separate section outlining options the technical team will consider. Allow for some open-ended proposals from suppliers for these additional options, but clearly delineate the possibility and any parameters to consider. An example would be if a company is bidding out their drug and alcohol testing program and would consider adding background checks into the scope of work if a supplier provided both. Or there are core tests the company needs done for policy and compliance, but they would consider additional tests as technology and testing methods change over time.

Note: When running the commercial evaluation on suppliers, consider leaving these additions out for at least the initial price evaluation. If doing an e-auction as your best-and-final-offer negotiation, make sure the core scope is where suppliers compete in the auction and then the additional options are either a separate part of the auction (such as a separate lot) or it is clear the RFP pricing will be what holds firm for a contract. Pulling things into line-item options can also be a way for suppliers to compete on a more level playing field as they pull these non-core options out of their competitive offering.

RFIs and RFPs

So what about when a technical team truly doesn’t know what is available, what they want, or how the supplier industry typically structures the offering? This is fairly common when a company is purchasing something for the first time (like a new service or technology), and is why Requests for Information (RFIs) are common. An RFI is the exception to the “no long lists of questions” guideline. Be aware, however, that in many categories suppliers will not respond to an RFI. They are a lot of work with less opportunity for payoff. Instead of an RFI, consider approaching target suppliers for a video call where the team can ask questions about the offering and formulate their scope of work. This may or may not include a demo, but it certainly should not include pricing. If the team needs to gather pricing, have the procurement rep gather that info as a range from suppliers separately to ensure process fairness. The technical team should write their scope without knowing supplier pricing.

Making Bids Monetarily Appealing

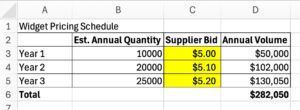

One of the most common issues I see with an RFP is not making the full value of the bid visible to the suppliers. By this I mean a buyer will ask for the price per unit (per hour, per widget, etc.), but either won’t estimate the annual quantity or won’t do the math to translate that annual quantity into an annual volume. For example, I offer three scenarios where a company wants to buy a widget and they send out an RFP to their typical suppliers for the widget with a full specification attached:

- The suppliers send back quotes on their own paper, bidding $5.00 for that widget. A primary supplier doesn’t even send a response.

- The buyer includes in the scope of work an estimated annual volume of 10,000 widgets, to be ordered weekly through the year. This time the buyer gets more responses, including from the primary supplier. When negotiating their final price, the buyer discloses a willingness to offer a 3-year contract for the widget and that volume is expected to go up to 20,000 in year 2 and 25,000 in year 3. (Note this is using the “rule-changing” negotiation tools to improve the outcome).

- In this last scenario, the buyer sends out a simple spreadsheet to serve as a pricing schedule and make it simpler to gather bid responses. They include the annual quantities and highlight the boxes for the supplier to put their year 1, year 2, and year 3 pricing. The built-in math on the spreadsheet then totals the supplier’s bids, making it clear this business is worth almost $300,000 to the supplier if they raise prices 2% each year. The buyer has gained more interested suppliers (and more interested sales teams if they are paid on commission) as well as the ability to negotiate pricing for future years and lock that pricing down. Simply doing the math makes the bid more appealing and the opportunity more visible.

This same principle also applies to hourly rates, which is part of why a buyer should always try to estimate quantities for hourly rates if at all possible.

Consider when publishing an RFP how to maximize its appeal for the sales team to get the best results. Respecting the sales team’s time can pay dividends in the long term–both relationally and monetarily. If you’d like to talk about your RFP approach, let’s chat.