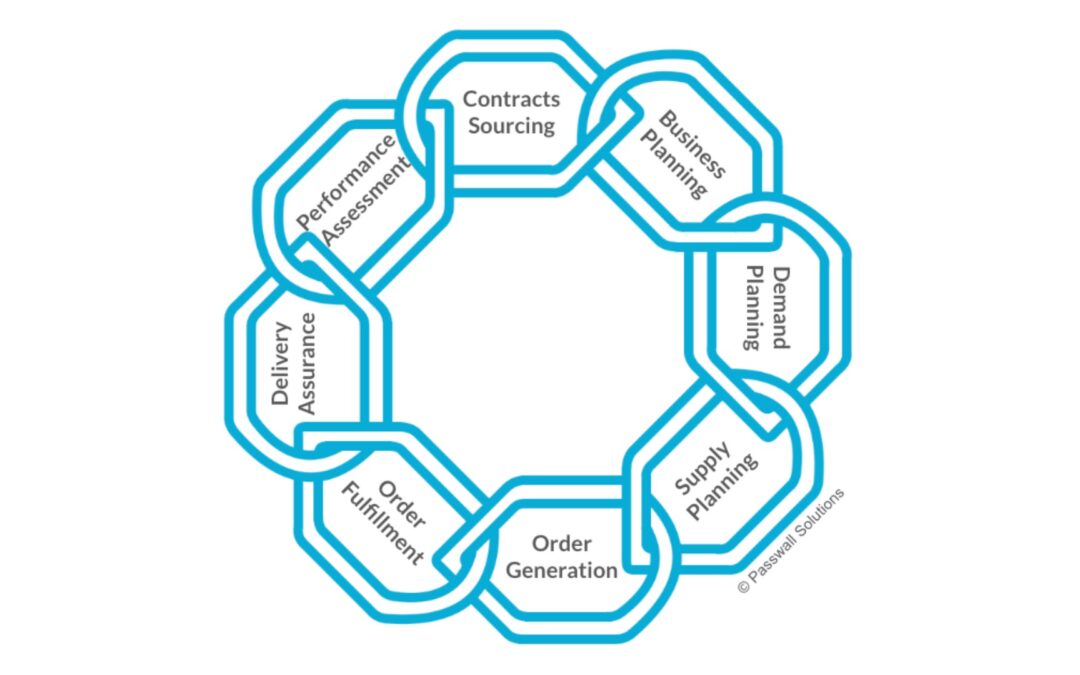

Unveiling the Dynamics of the Supply Chain Cycle: Enhancing Delivery Assurance and Performance Assessment

In the intricate dance of the supply chain cycle, the pivotal roles of delivery assurance and performance assessment come into focus. While often discussed as the concluding components, they seamlessly loop back into the cycle, reinforcing the importance of a well-coordinated and dynamic supply chain.

Delivery Assurance

Delivery assurance is a critical facet, ensuring timely and accurate delivery of materials and services. Unfortunately, some supply chains consider their duty fulfilled upon entering orders into the ERP system, addressing late purchase orders only when they become critical. Proactive measures in delivery assurance are paramount, particularly in industries with tight manufacturing schedules, where delays can disrupt production lines.

Warehouse Execution and Outbound Logistics

Internally, warehouse execution plays a crucial role in delivery assurance. Despite warehouses often reporting to operations rather than the supply chain, collaboration is essential to meet internal stakeholders’ needs. This involves supporting inventory efforts, conducting root cause analyses, and maintaining open communication between supply chain and warehouse teams. For companies with a heavy outbound logistics workstream, the supply chain team can assist with reusing packaging materials and coordinating back hauls with incoming logistics freight carriers. Collaboration, rather than finger-pointing, is key for success.

Exception Management

Externally, exception management tackles the question of how to respond when deliveries fall short. Solid contracts, demand planning, and purchase orders lay the foundation for dealing with incidents effectively. Responses may include rebates, engaging third-party distributors, or, as a last resort, rebidding supplier contracts. I reserve rebidding the work as a last resort not because it erodes a supplier relationship but because in a well-managed supply chain bid timing is based on market forces. Moving the timing of a commodity’s bid event due to poor supplier performance undermines the holistic approach of bidding at the right time for the business and the larger market, and can cause more of a ripple effect through the supply chain than the exception warranted. It’s important to note that exception management extends beyond materials to include services, such as software-as-a-service, requiring a similar proactive approach to prevent business disruptions.

Performance Assessment

Performance assessment is a universal practice in companies, employing Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) or other frameworks to measure and enhance overall performance. The often truncated or misquoted saying from Peter Drucker is, “What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organization to do so.” The crucial aspect lies in selecting relevant metrics aligned with company values and communicating them effectively.

Internal Metrics

Internally, supply chain metrics must align with the organization’s goals and values. It is tempting to measure only the metrics the supply chain considers important, or on metrics that are “easy” to measure. If the company has a core value to improve the environment, the supply chain should have a metric to improve supplier emissions, recycle packaging, or some other related goal. Similarly, if the company is not overly concerned with cash flow or tying up capital (such as in a utility), calls to measure and improve inventory turns will fall on deaf ears. If stakeholders are concerned about the amount of time it takes to receive requested bid results and contracts, the supply chain must measure those timeframes and work to increase process transparency. Automation is key to measuring metrics efficiently, ensuring everyone on the supply chain team comprehends and contributes to achieving them. Adjustments should be made based on measured outcomes.

Supplier Scorecards

Externally, supplier scorecards are instrumental in improving relationships. Rather than being wielded as weapons, these scorecards should serve as frameworks for regular communication and collaboration. Certain metrics are somewhat obligatory on a supplier scorecard, such as percentage of on-time delivery and responsiveness to issues. However, supplier scorecards are often bloated with irrelevant metrics for that supplier’s industry, items that are difficult to measure clearly, and measures that do not align with company values. A scorecard with only four key metrics that truly matter to the company is far more powerful than a diluted mess of twenty metrics that could never be covered in a half hour meeting.

Companies also often try to apply scorecards to all suppliers or a vast majority. Each commodity/category manager should be using their scorecards to focus on three or four suppliers that truly matter to the business and serve as strategic partners. The relevant parties should review scorecards frequently–quarterly or even monthly–to ensure they are driving results. The relevant parties may even include key stakeholders from sales or operations to provide clearer feedback and improve the relationship. Focus on a few key metrics that truly matter, making the scorecards clear, concise, and relevant to strategic suppliers.

Conclusion

The supply chain cycle, with its intricate links, continuously evolves. After performance assessment, the cycle recommences with contracts and sourcing, informed by internal metrics and supplier scorecards. Sourcing and contracting efforts lead into business, demand and supply planning, where the supply chain gathers and deploys forecasts to proactively ensure delivery. The plans become orders in order generation and fulfillment, when suppliers and businesses fulfill the commitments of contracting and planning. Then the delivery assurance and performance management links provide the necessary feedback loops, closing the cycle to begin again.

A harmonious supply chain cycle, where each link strengthens the process, is the hallmark of success. Conversely, a broken supply chain signals the need for a comprehensive evaluation, identifying and fortifying the weak link to restore strength, transparency, and support.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our series on the supply chain cycle. Please reach out to Passwall Solutions for a free half-hour assessment of your strong and weak links, and determine the next steps to building your world-class supply chain.