In a deep dive training into Sourcing with a client recently, I mentioned the phrase “tail spend” and was met with a few blank looks. Tail spend is one of those procurement terms that we don’t realize is jargon, and this was a group of people new to the profession. So today’s article we’ll cover what tail spend is and what you can do about it.

What is Tail Spend?

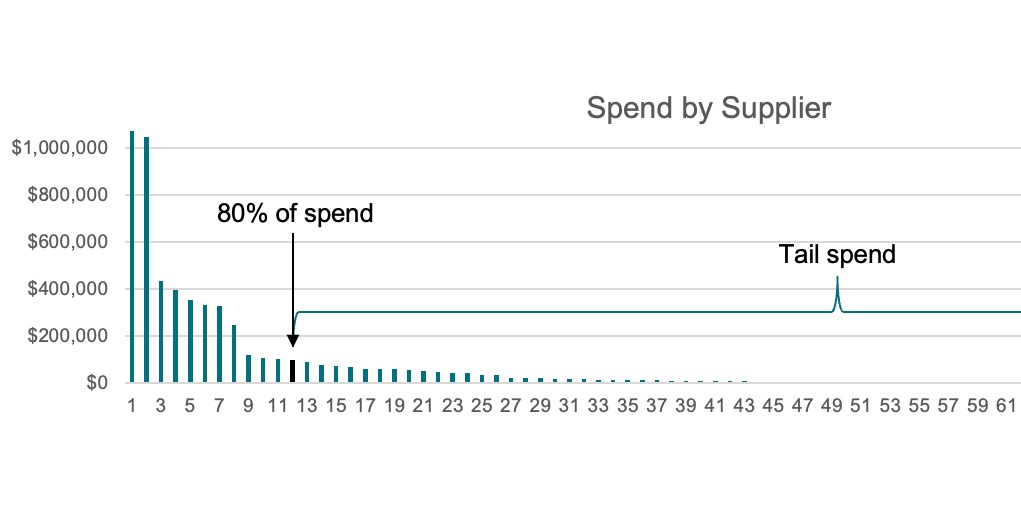

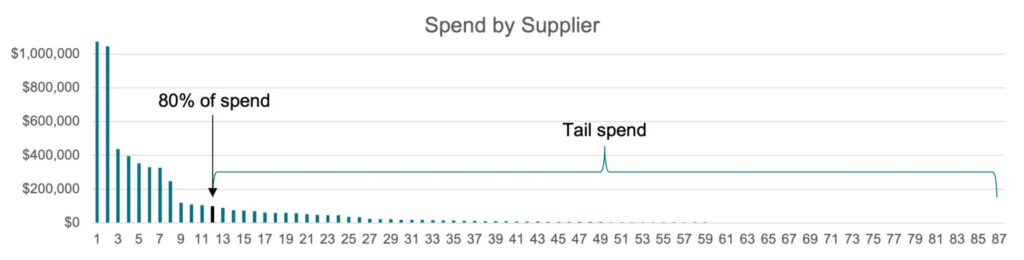

Tail Spend is the low risk, low dollar purchasing spend. Every company has at least some tail spend, and it’s basically what appears on the right side of the “spend vs. supplier” graph. This graph shows the suppliers, ranked by their spend amount, on the x-axis and the amount of annual spend with each supplier on the y-axis. The graphic tied to this article is real data from one of my clients, and most spend vs. supplier graphs look a lot like this one. There are usually a couple of suppliers with most of the spend, and then it quickly drops off from there. If you’ve never made this graph, I recommend it.

Side note: to create the spend vs. supplier graph, get your ERP system to produce a PO line report that shows supplier name (or number), quantity purchased, and price per item. Some ERPs want to also include the total PO value and some you have to calculate the total PO line value by multiplying the quantity purchased by the price per item. Most ERPs already have a report built-in to send this information into an Excel file. I recommend using a year of spend to create this report if you can; if that is too much data, use the last 6 months. Then create a pivot table with the Suppliers in the “rows” box and the sum of PO line spend in the “Values” box. Sort by highest total PO line spend and graph the result as a bar graph.

There are a couple of different ways to draw the line on where tail spend starts, here are the most common:

- The bottom 20% of spend – if you add up all of your spend and then figure out how many suppliers make up 80% of your spend, the remaining suppliers are considered tail spend. It often surprises companies just how many suppliers this is, and is usually 80% of your suppliers. For example, if a company has $10 million in spend and 400 suppliers, I would expect that $8 million of their spend is in 80 suppliers and the remaining $2 million is spread across the other 320 suppliers. This is also known as the “80/20 rule” or “Pareto Principle” and it constantly surprises me how often it applies. One drawback to this method is that you will always have a lot of tail spend suppliers, and it can be disheartening to not make a big dent in the number of suppliers during a tail spend reduction initiative.

- Spend below a set threshold – this is all suppliers with annual spend less than a set amount of money. The amount will vary based on the size of the business, but it might be $1000, $5000, or $10,000 for a small or medium-sized manufacturer. One way to approach this is to look for drop-offs in spend from suppliers or figure out where that 80/20 spend line is and use that as a guide to set the threshold. One nice thing about this method is that you can set that threshold based on what it costs to maintain a supplier or based on business criteria.

- C Suppliers – many companies have suppliers they have independently classified as low risk and tactical instead of strategic, typically known as “C” suppliers in an A, B, C classification. A suppliers are strategic and high spend/high inventory turnover, B suppliers are in the middle for spend/risk/inventory turnover, and C suppliers are the remainder. Similar to the “bottom 20%” rule, there will always be C suppliers and the definition simply morphs over time as suppliers in this classification are moved out of the supply chain. This method also requires an independent classification system, which is a lot of work if you don’t already have one.

Cost of a Supplier

So why do we care about reducing tail spend suppliers? Why not just let them hang out there at the bottom of our spend forever? The short answer is: because suppliers cost money. I have seen companies value the cost of having a supplier anywhere between $1000 per year and $50,000 per year depending on the purchasing company. Factors that go into this cost include:

- ERP system management – keeping the supplier information (address, bank account, tax forms, payment terms, etc.) up-to-date in the system as part of keeping your Enterprise Resource Planning system clean. This doubles if you have a separate supplier resource management system that is not automatically tied to your ERP.

- Electronic storage costs – while electronic storage for a company is generally pretty inexpensive, it also adds up. Companies have to keep purchase orders for years as part of records retention and taxes, and there is a hard cost to the megabytes and terabytes being used to store that data. This goes up if the company rents server space from a company like AWS or has a cloud-based ERP system that charges based on space used. Most businesses don’t have their own servers, so this is an ongoing cost instead of a capital cost.

- Administrative costs – these are labor costs to meet with suppliers regularly, field calls from them asking about new business, and analyzing their data. Most of these are very “soft” costs like ERP system management, but category managers and analysts spending time with tail spend suppliers are not spending their time with the larger or more strategic suppliers. Usually these costs are lower for tail spend suppliers, but they are not zero.

- Contracting expenses – this is the cost to negotiate a contract, both in labor from the procurement or contract management team and the legal costs. If the company has an in-house legal team, this expense is a little lower, and a trained contract manager conducting the bulk of the negotiation can also reduce the total expense over that of an attorney. Now you’re probably thinking, “But tail spend suppliers don’t have contracts!” Any supplier who does not have a contract does have a higher risk cost. The reason we put contracts in place is to lower this risk and therefore lower the costs of insurance, liability, warranty, and payment terms (among others).

- Volume discount opportunity costs – Important customers get better discounts and more attention. The best way to become an important customer to suppliers is to spend more with them. While this doesn’t strictly belong under supplier costs, it is something to think about when setting thresholds and managing suppliers. There is an opportunity cost with larger suppliers when you’re giving some of their business to smaller spend suppliers.

Even a back-of-the-envelope calculation on these expenses can help you decide what to tackle first and where to set your thresholds for tail spend. Knowing what suppliers cost you can help validate a project to reduce supplier numbers.

Reducing Tail Spend

Now that you’ve done a little research into which suppliers are in your tail spend and what the suppliers cost you, how do you reduce tail spend? Here are a few approaches:

- Remove/deactivate zero and low spend suppliers. There are probably several suppliers at the very bottom of the list with very little spend in the last year (perhaps less than $100). Deactivate these in the system and require that any purchase desired from those suppliers must go through the supplier add process as if they were a new supplier. This includes justifying the purchase, validating that existing suppliers cannot provide the product or service, and that other purchasing methods are not the right option for this supplier. This is a place where good bureaucracy can cause people to pause and instead move purchases to suppliers with more spend that care more about you as a business.

- Consolidate suppliers. This is the art of taking multiple tail spend suppliers and combining their business into one bundle. You can run a Request for Proposal for this business, or simply choose a supplier with a good contract or good relationship to receive the business. Bundling tail spend work together results in being more important to fewer suppliers, leveraging that volume, and reducing your total number of suppliers. Often supplier consolidation is into a distributor, and you will pay a little more (usually 5-15%) for that distributor to handle the supplier for you and manage the inventory.

- Move to purchasing cards. Intentionally moving spend to purchasing cards/company credit cards can be controversial and tricky. For suppliers you are paying less than $100 or $1000 per year, it might make sense to simply make purchases on credit cards. The trick here is continuing to govern that purchasing card usage well so it does not get out of control. Keep good rules on when a purchasing card is allowed and when the business needs to use purchase orders to order materials and services.

- Automation and blanket POs. The automation or blanket purchase order strategy doesn’t truly remove suppliers, but it makes the suppliers you are using less of an administrative burden. The approach here is to automate tail spend suppliers and minimize the amount of time, effort, and storage they require. This is especially useful when a supplier has a patented or otherwise protected part that they are not willing to work with a distributor for, or when you are cutting one supplier a large number of POs for low cost items.

Tail spend is an interesting and sometimes controversial topic, and there is no one answer on how to approach it. The right answer for your business might be to even ignore it in the short term, but a more strategic and mature procurement team will naturally start to tackle tail spend as part of the overall strategy. If you’d like to talk through making a plan for your tail spend, let’s chat.