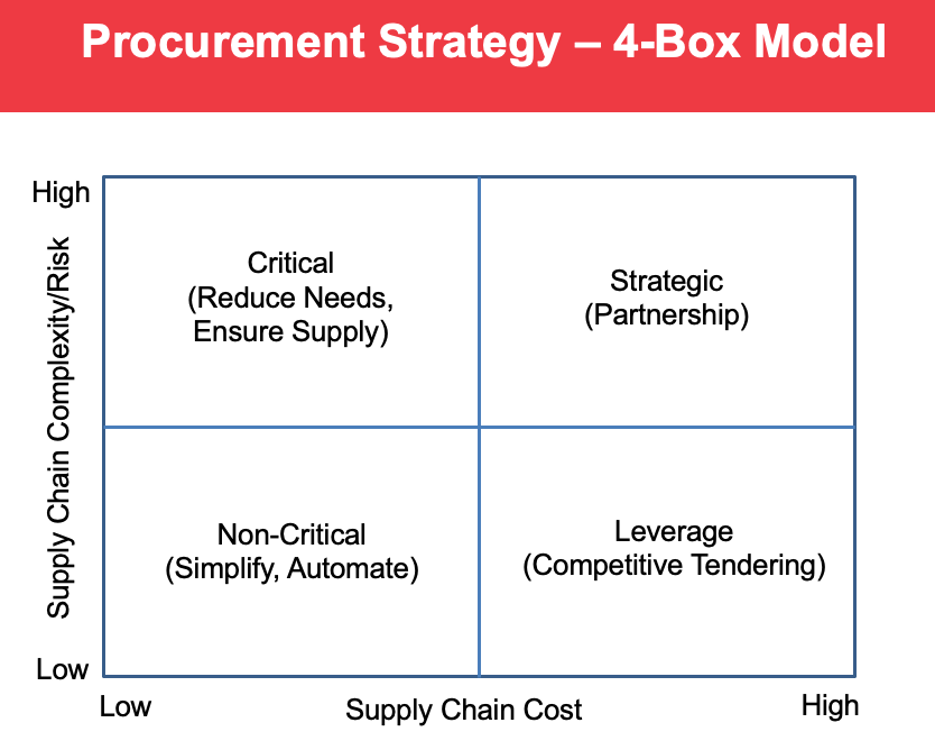

I once had a supervisor who was obsessed with what he called “the 4-box model” of procurement. His version graphed supply chain complexity/risk on the y-axis and supply chain cost on the x-axis, classifying suppliers into one of the four resulting quadrants. Low cost and low risk suppliers were Non-critical, low cost and high risk suppliers were Critical, high cost and low risk suppliers were Leverage, and high cost and high risk suppliers were Strategic. He was not a supply chain major and was two weeks into managing his first supply chain team. While he wasn’t too far off from one of the central principles of procurement, what he really wanted was a Kraljic Matrix. For today’s article, let’s talk about the differences between this “4-box model”, a Kraljic Matrix, and the Kearney Chessboard. More importantly, let’s talk about how to use them to improve supply chain value, how to present their data to executives, and why this tool from 1983 is still relevant today.

Differences Between 4-box Model, Kraljic Matrix, and Kearney Chessboard

Differences Between 4-box Model, Kraljic Matrix, and Kearney Chessboard

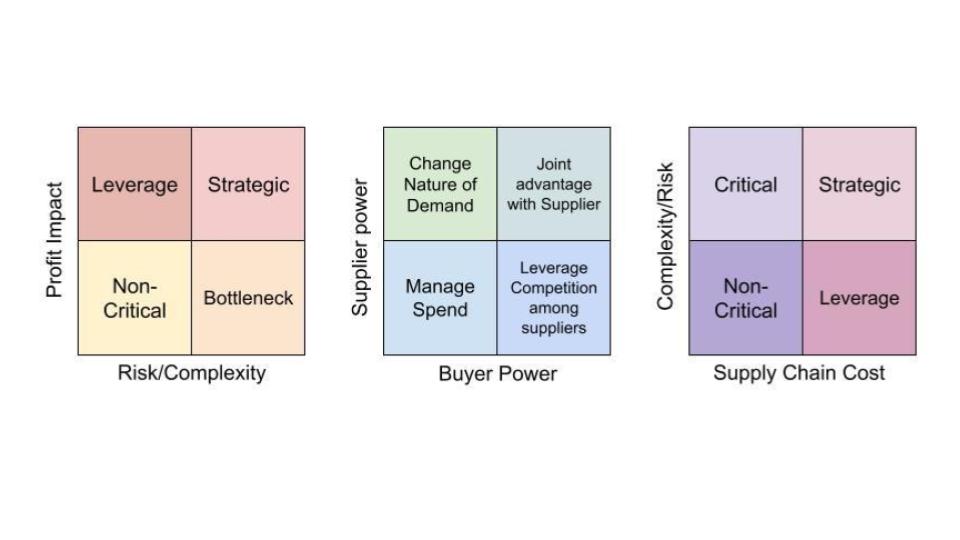

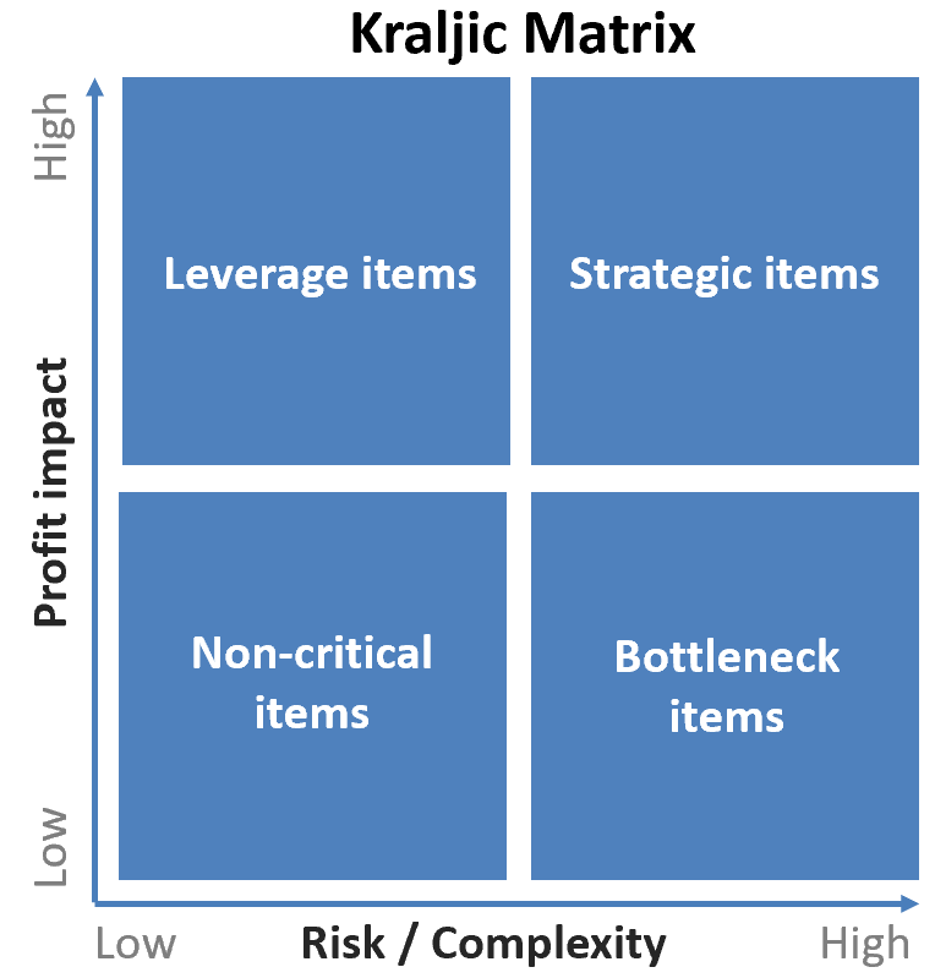

I confess I’m not sure where my former supervisor’s “4-box model” came from, although it does appear to be a slight modification on the Kraljic Matrix. The Kraljic Matrix was introduced by Peter Kraljic in 1983 in a Harvard Business Review article titled Purchasing Must Become Supply Management. His version looks more like this:

It is worth noting the two major differences: Kraljic uses “profit impact” instead of “cost” and calls the high risk and low profit impact items “bottleneck” instead of “critical.” You might be thinking these differences seem small, but they make a big difference in the procurement mindset. First, we are still actively debating on LinkedIn how much procurement needs to shift toward thinking about Profit and Loss Statements instead of just cost savings. The fact that Mr. Kraljic was talking about profit impact (and not cost savings) back in 1983 blows my mind and makes me realize how hard this industry is to change. Second, calling items “bottleneck” instead of “critical” really changes how we think about them. Bottlenecks are to be cleared out and removed, critical items are to be treated carefully like highly breakable glass. The other interesting thing about the Kraljic Matrix is that Mr. Kraljic used it for purchases (categories), not suppliers. Both work well with his matrix, but I think it’s interesting how common use of the Kraljic Matrix has shifted toward suppliers in most procurement teams.

Side note: I confess sometimes I misspell this “Krajlic Matrix.” I’m sure I have in some of my previous articles. My apologies, I’ll try to get it right. I also once worked with a German procurement consultancy and the way they said Kraljic was simply beautiful. They used consonants English simply doesn’t have and it didn’t sound awkward when they say it. The best description of how they pronounced it, without those lovely noises that work better in their accents, was crawl-jick. That is about as reasonable an approximation as I can get with my American-native tongue!

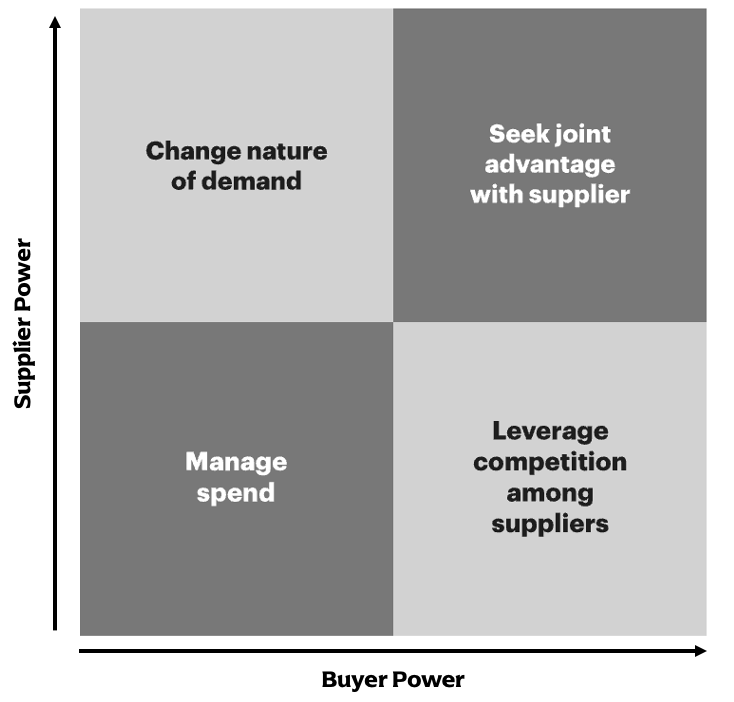

Now the Kearney Chessboard, also known as the Purchasing Chessboard, is similar to a Kraljic Matrix in that it centers on a 4-quadrant grid. It is also prescriptive in telling a procurement professional how to handle the supplier/category to maximize value. However, the x-axis in this case is buyer power and the y-axis is supplier power. With low buyer and supplier power, the recommendation is to simply manage the spend. With low buyer power but high supplier power, the recommendation is to change the nature of the demand, perhaps by bundling or breaking a purchased item into components with more competition available. With low supplier power but high buyer power, the recommendation is to leverage competition among suppliers (this is where Requests for Proposal and E-auctions thrive). Lastly, high buyer and supplier power lead to a need to partner with a supplier to seek joint advantage (like gainsharing or performance-based incentives).

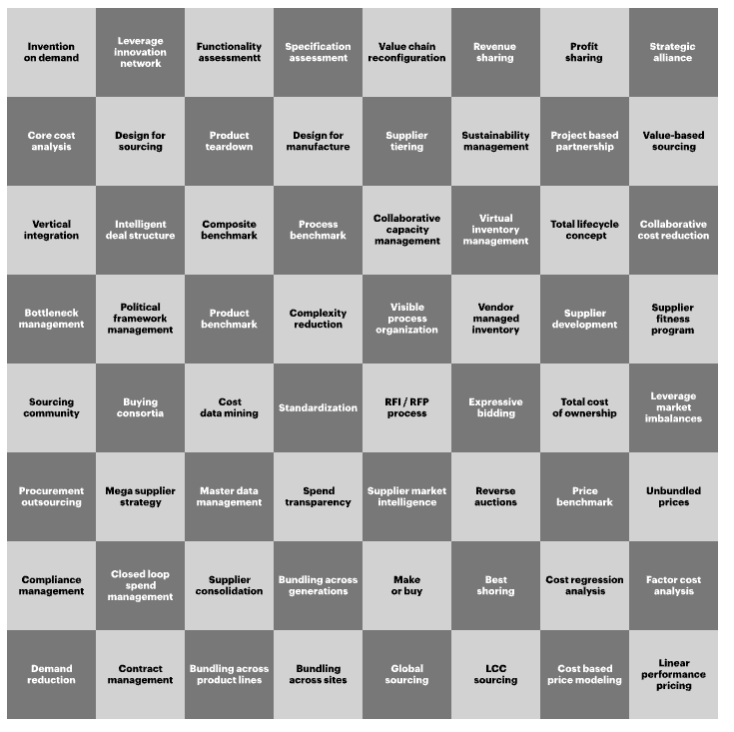

One of the things I really love about the Kearney Chessboard (which is actually the model I had been using with my team when that new boss came in with his 4-box model) is that they subdivide each quadrant into sixteen more specific methods.

These still follow the main four quadrants, but are more granular in what to do within the nuances of buyer and supplier power. If you are interested, I have an Excel-based tool that will help you categorize your suppliers (or categories if you prefer) within this matrix that I can send you if you send an email to Janice@passwallsolutions.com and reference this article. I’ve thought about posting it to my website, but would love a few beta testers on it first before I push it out as a more polished product.

Improving Supply Chain Value

Ultimately classifying suppliers within these matrices is useless unless a procurement team does something with the information. All of the models here are useful for the following things:

Determining Category Strategy

Whether you use a matrix for suppliers or categories, either can inform your category strategy. Understanding your suppliers within a category is the first step to improving the purchasing position and building value within that category. All of these matrices will help you determine how much competition is available, which negotiation technique(s) or lever(s) to use, and give some insight into the long-term and short-term impacts of your strategy decisions.

Focusing Procurement Energy

We all only have so much time to devote to maximizing the value of our efforts. In procurement, I’ve never met a team that said they had enough resources and time to do every one of their purchases the justice it deserves. Therefore, these matrices can help us figure out where to focus the time and energy we do have. There is little value in focusing efforts in the “low-low” category on any of these matrices, so it is useful to know which categories and suppliers occupy that quadrant. That way we can focus on two or more of the other quadrants and maximize our efficiency.

Communicating Strategy to Stakeholders

If communicating with executives, I would generally stick to the quadrant models of these matrices. This can be an excellent way to organize all of the complicated pieces of procurement into an understandable model without leaving out some of the “softer” pieces of procurement strategy (such as risk or global forces). If communicating to a technical team, especially one made of engineers, you may find that the 64-section model helps them understand why you’re deciding to approach suppliers the way you are. And even why it’s important they not give as much information to suppliers (such as their favorite or incumbent supplier) because that information changes the supplier and buyer power dynamic which then changes strategy. As Simon Sinek says, “Start with Why” when trying to bring someone to your way of thinking.

Hopefully today’s article has gotten you thinking about tools you’re using in setting your procurement strategies. While these tools are definitely not new, they are still very much relevant and useful due to their flexibility. If you don’t use them regularly, try them out when building out your next negotiation or category strategy and see if they help bring clarity to a murky supply chain world.

If you would like to talk about these matrices and how your team is using them, let’s chat. If you’d like to get these articles weekly straight to your inbox and never miss one, sign up for my newsletter.

My book, Transform Procurement: The Value of E-auctions is now available in ebook, paperback and even hardcover format: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0F79T6F25