This morning as I checked my inbox, I had a survey waiting for me from World Commerce and Contracting. The survey sparked me because it asked a set of questions about the purposes of contracts, and I found my answers highly varied across the questions. I will note that I am a believer in contracts and spend more than nine years working for one of the most risk-averse businesses in the US. It’s sufficiently risk-averse that if you look up quotes by its founder, one of the most famous is about reputation.

This article is about the purposes of contracts and how each of these goals might manifest in contract documentation or handling.

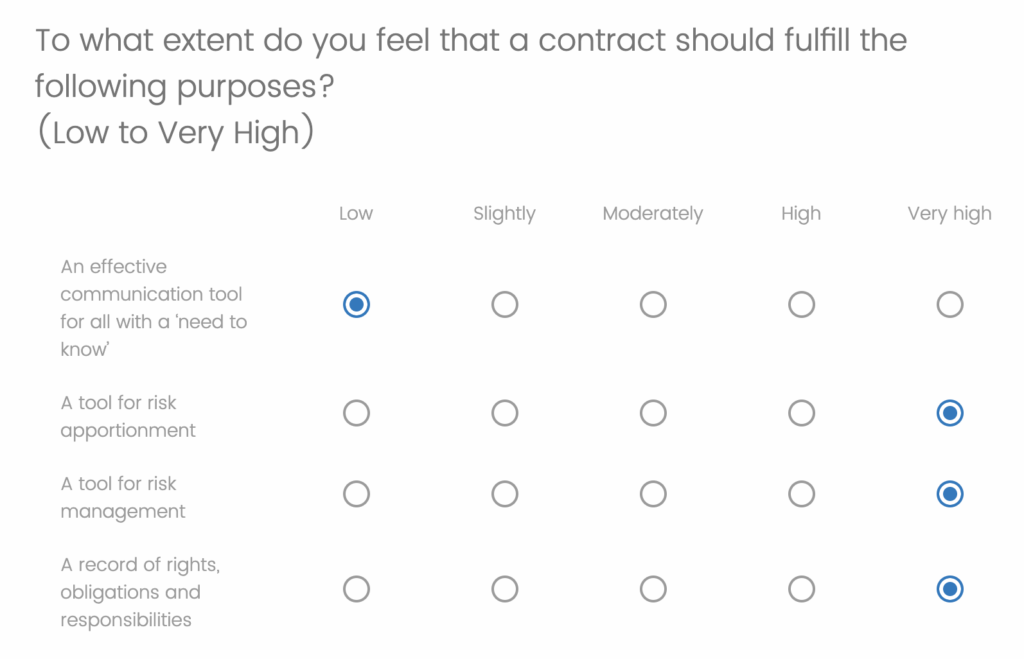

Communication

To what extent is a contract an effective communication tool for all with a “need to know”? My initial reaction to this first question was: Yikes. A contract as a communication tool? That sounds like a terrible way to manage a contract. Most contracts are lengthy and the contract itself is far too long for executives to read through. That being said, it is a best practice to create some sort of one-page executive summary to highlight key areas of benefit and risk (tips on doing that found here). So if contracts are a communication tool in your organization, ask if the right people are really receiving the right information.

Risk Apportionment and Management

The next two questions asked about the purposes of contracts for risk apportionment and management. From where I sit, these are the two primary purposes of a contract. All else, especially commercial considerations, hinges on the allocation and reduction of risk inherent in the contracting process where the “easiest” way to reduce cost is to take on more risk. A contract is a formalization of the agreement of how much risk the buyer and supplier take on (in the form of liability, responsibility for cybersecurity, warranty, environmental considerations, insurance, etc.) and the commensurate reward for those risks (primarily in the pricing schedule). During a negotiation, sometimes one risk is exchanged for another. For example, a company with a very robust cybersecurity program might take on more cybersecurity risk and liability in exchange for a better warranty clause. In this example there was not a direct commercial reward for the risk, but ultimately the party that can take on the risk at a lower cost benefits from assuming those risks in exchange for shedding the higher-cost risks. Each clause in a contract, other than those required for structure and legality, should speak to either risk or reward.

Record

The next question asked: to what extent is a contract a record of rights, obligations and responsibilities? This is the more administrative function of a contract, where the contract codifies what the buyer and supplier both agreed to. Many contracts also highlight the rights and obligations already determined by law, such as applicable import tariffs or governing bodies. While this can feel redundant, it is often needed for clarity. Especially with international contracts where multiple governing organizations might determine regulations.

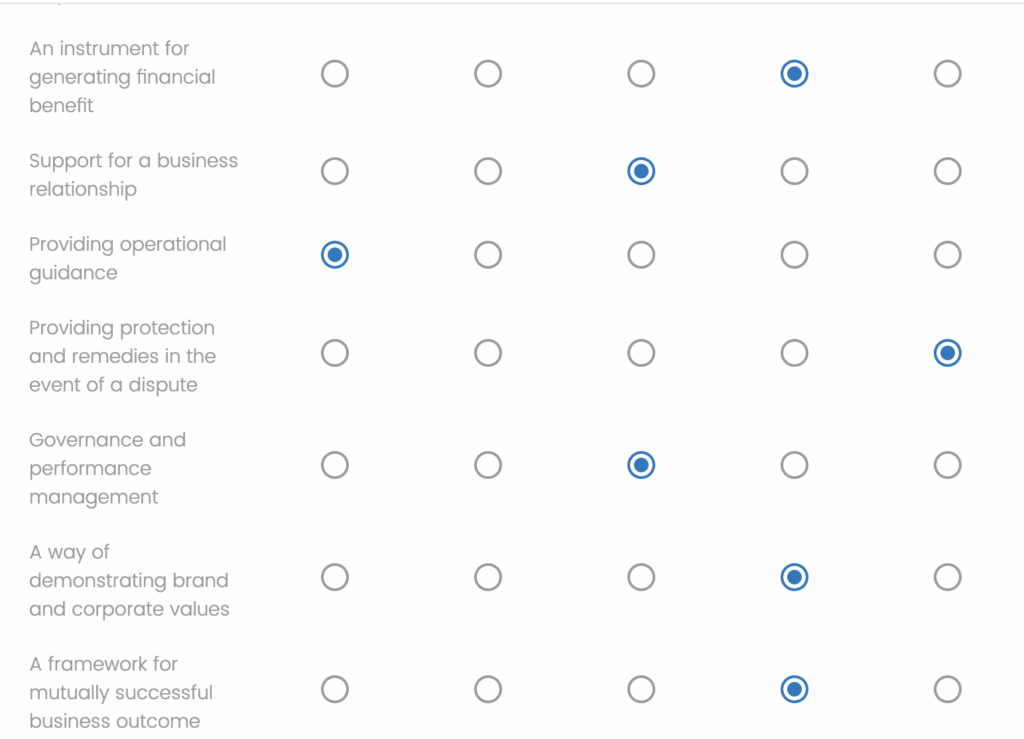

Financial Benefit

The next question asked how much a contract is an instrument for generating financial benefit. This question ultimately comes back to the risk/reward balance already discussed. A well-written and well-negotiated contract increases the financial reward for the party who takes on more risk. While negotiations are seldom so simple, each negotiating party should be wary of taking on risk without some sort of reward.

Business Relationship

The next question asked about the purpose of a contract as support for a business relationship. Oh, how I wish this was a contract’s purpose. As a supply chain/procurement professional, I would dearly love to simply negotiate and ink the contract and have that be the majority of what is needed to govern my supplier relationships. However, this gives the contract far too much credit. Supplier relationships are built and supported through consistent, day-in and day-out activity and engagement. A supplier scorecard (done well) has far more impact and support on the relationship than a contract. I have seen more buyer-supplier relationships break down over contract terms than supported. While a truly great contract can provide some support to the relationship, it is closer to a last line of defense. A contract is a bulwark against disengagement; and is a commitment, not a support.

Operational Guidance

I found the next question asking about the purpose of providing operational guidance intriguing. I ultimately rated it low because I consider the contract primarily in the contract terms and perhaps pricing schedule. A contract often includes a project scope/statement of work, which is key in setting guardrails around the engagement, but should not dictate how either party runs their operation. The running of an operation does determine the level of risk each party is willing to take on, but the contract must speak to results. Dictating the “how” in a contract can often be detrimental to the best way to run an operation, and adds bureaucracy and inefficiency. A contract should allow the maximum possible latitude in operational methods while holding each party accountable for results.

Disputes

The next question asked about the purpose of contracts in providing protection and remedies in the event of a dispute. This is almost as high in contract priority as the risk allocation, as it dictates the “eject” button for the contract (and maybe the business relationship). That being said, a contract dispute should be a last resort. A clearly-written contract that both parties are able to meet will seldom result in a dispute. To keep it out of a dispute, whoever manages the contract has to keep a dialog with the supplier and vice versa. I always think of a contract dispute as a little like an employee Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) and contract termination like firing an employee. Unless things have gone really wrong, disputes are a last resort and must be treated as a way to get the contract back on track (not the first step in termination). This means the dispute process must be very clear in the contract terms and should more likely result in a contract amendment or a course correction than in termination. If your disputes are constantly resulting in terminations, it’s time to look critically at your standard dispute clause.

Governance and Performance Management

The next question asked about the purpose of governance and performance management in contracts. My reaction to this is: half yes. Contracts should provide governance, but not performance management. As mentioned in the Business Relationship section of this article, performance management is driven primarily by the relationship and supplier scorecards.

Brand and Corporate Values

The next question asked about the purpose for contracts in demonstrating brand and corporate values. My initial reaction to this was: No, of course not. But that’s clearly not correct and I simply had never directly contemplated this angle. Of course a contract is infused with a company’s brand and corporate values. What a company values directly impacts what goes into their contract template, what concessions they will make, and which clauses they add or subtract over time. I remember working hard with our Chief Diversity Officer and Chief Sustainability Officer to add a code of conduct to our supplier documents, and then making sure each element was covered consistently by our contract terms. Even when subtle, a contract does convey a company’s brand and values.

Mutually Successful Business Outcome

The last question asked: to what extent do you feel a contract should fulfill the purpose as a framework for mutually successful business outcomes? While a contract should certainly accomplish this purpose, I didn’t rate this item highest on the scale. This is because a contract cannot carry the burden of a mutually successful business outcome alone. A contract isn’t even the majority of this burden. That burden rests with the people and interactions that make up the buyer-supplier relationship. A mutually successful business outcome occurs when both parties work together to accomplish the work, at the agreed-upon price, in the most efficient way, and in the established timeframes. The contract may codify these expectations on both parties, but it cannot actually accomplish the goal.

Exploring the purposes of a contract was an interesting exercise, and may be worth exploring for your own templates. Or, if you’re still writing or establishing a template, you can ask which purposes serve you most. Perhaps my perception is colored by the organization I learned from. I’m struck by the similarity to the creation of anything–a contract, an RFP, a quilt, cooking a meal–what is this creation’s purpose? Who does it serve? Ask that question, and then build from there.